It was Thursday; a brisk spring morning at Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center, up in the mountains where it is nested. The Wildlife Program staff routinely start their day in the office before departing for wildlife health checks, facility walk-arounds, and daily preparations. Joe, the aviary coordinator, exhaled and pulled out his phone showing a fluffy, downy, baby owl with enchanting golden eyes. “Look at ‘em.” I, Paige, the director, seemed to inhale the sigh just released and understood the unspoken proposition. “Great Horned?” I asked. “Two to three weeks, imprinted, non-releasable.” Eyebrows raised, jaws dropped, hope flooded.

We gave ourselves forty-eight hours to let our heads catch up to our hearts and properly assess our readiness for an acquisition such as this. There was much to consider, primarily whether our freshly seated staff of four was in the right place to provide the necessary time, energy, and care to this developing ball of feathers. Ultimately, we’d seal our fate that this Great Horned Owlet would be the next ambassador welcomed to the Klingsberg Aviary.

Understanding the role of an ambassador animal helps us understand how to acquire it. Wildlife ambassadors build knowledge and understanding about species, the natural world, and contributions to conservation. They foster positive connections, emotions, attitudes, values, and empathy toward wildlife and wilderness areas. They promote awe, wonder, enjoyment, creativity, and inspiration and motivate pro-environmental behaviors, actions, and advocacy. This extremely impactful role must be employed with great consideration.

At wildlife education centers (or zoos), programs like ours develop what is called a Collection Plan. This Plan guides decision-making and management of the resident animals that will be acquired and cared for based on the program’s welfare resources, education strategy, and overall mission. We want to make sure we can support these animals at the species and individual levels, from their medical care, diet, and husbandry management to our behavioral training and preparation for educational programming. We also choose to focus on species native and local to Pennsylvania to ensure our ability to support their ethological needs year round. This also allows us to focus on the species our visitors may or may not know exist, but ultimately and intimately are connected to just by sharing home and habitat. We want to make sure the individual we are considering is capable of not just living, but flourishing within this unique lifestyle. Wildlife being deemed non-releasable by a rehab means the animal will require the form of support equal to why they could not be released back to the wild.

Our Plan intends for Shaver’s Creek to be the forever-home to the wildlife it takes in, whether they’ve been declared non-releasable from a wildlife rehabilitation center, are transferred pet confiscations from state agencies, or have been bred for conservation. This means we are charged with and have the honor of supporting each unique individual and their needs during their early, novice days at the Center, through days of welcoming visitors and participating in public programming, and to the delicate decisions revolving around end-of-life care. These commitments require a great deal of awareness and preparedness, as much as one can have when working with such curious creatures.

This owlet fit everything our Collection Plan requires. Great Horned Owls are charismatic and alluring, connecting with people of all ages and helping them to care about the species and their habitat. They support many conservation themes that protect wildlife and wilderness areas, like not using rodenticides or throwing apple cores to the side of the road (apple = prey, road = cars). Speaking of their prey, they also keep other primary and secondary consumers in check within their populations with their diverse diet and adaptable habitat range, making them a keystone species in the Keystone State. The owlet had not sustained injuries that would require extensive medical support, in fact, he had not sustained any. He was found on the ground in the forest by a human who, like many humans, wanted to care for the baby by bringing it home. Unfortunately though, like many humans, this one did not understand the neurological developments happening at this critical owl age and he imprinted the baby. The imprinted owlet saw humans as his resource for survival rather than his parents, or the foster dad at the rehab that he was eventually taken to. His story could help people understand what they SHOULD do when they come across orphaned, injured, or otherwise discovered wildlife and have concerns for their well-being — which is to call your local wildlife rehabilitation center for help! (Sidescript: It is common for baby birds to end up on the ground throughout the fledging process, meaning mom or dad are likely nearby to keep a watchful eye and deliver dinner until the baby climbs back up to the comfort of the nest.) Lastly, being such a young and human-oriented owl would help him develop into an ambassador that should flourish at an educational facility like ours for a lifetime.

With our decision made, we prepared. Like many expectant caregivers, we fitted his living space — nest boxes, perches and platforms, a pond, and a “crib cam.” We drew up lists of names that might befit this yellow-eyed puffball that would grow to represent one of the most revered predators on earth. After paperwork, medical exams, conversations with industry experts and mentors (thank you endlessly, Hillary!), and a 14-hour car ride, Joe and I arrived at the rehabilitation center that had reached out to us just four weeks prior.

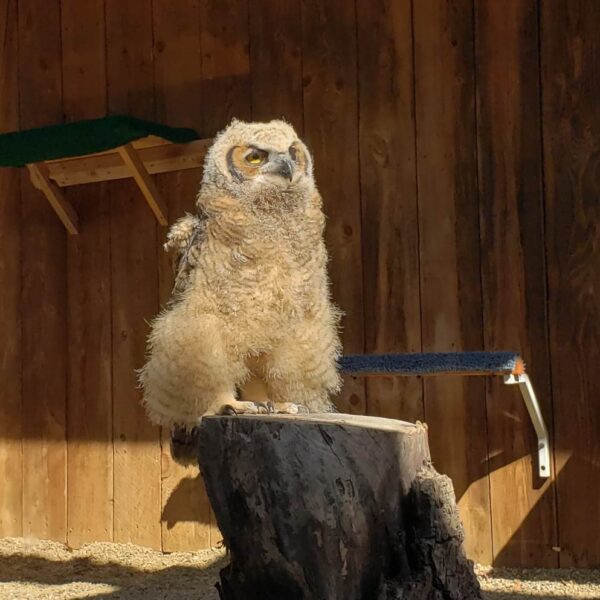

The owl settled into Shaver’s Creek just as he transitioned into his mature buff and brown adult plumage. His most frequent activities included eating, naps, pouncing on pinecones, more eating, and fine-tuning his haphazard flight skills to precision and poise. Through all of these activities, he looked to his new caretakers, the Center’s Wildlife Program staff, for resources, opportunity, and relation. It is our job (and highest honor) to guide the animals who call Shaver’s Creek home as they develop the skills necessary to educate our community about the beloved local wildlife and wilderness areas of Pennsylvania.

After much consideration, we decided to name this yellow-eyed, buff and brown–feathered boy Sunny. Being a Great Horned Owl, his species is crepuscular, hunting at dawn and dusk, the first and last moments of sunlight. He’s also brought so much brightness to us!

We have adored watching Sunny grow. When he first arrived, he was exploring the world, as babies do, with his mouth. He wanted to pick up sticks, pinecones, his own feathers, and our fingers with his beak to explore and understand. He was mastering his flight paths and landing skills. His most common vocalization at the time was his baby-beg, reminding us diligently when his feeding time was (it was always “immediately!”). Now, he keeps a watchful eye on the sky for migrating raptors and airplanes overhead. He is currently practicing flying through two trainers as they create a large hoop with their arms (with slight reservation and extreme precision). He has recently found his voice, often landing on a platform nearby his trainer with a “hoo hooo,” distinctly forming his own identifiable intonations. We are beyond excited to continue introducing him to our community and building his skills and confidence for public programming.

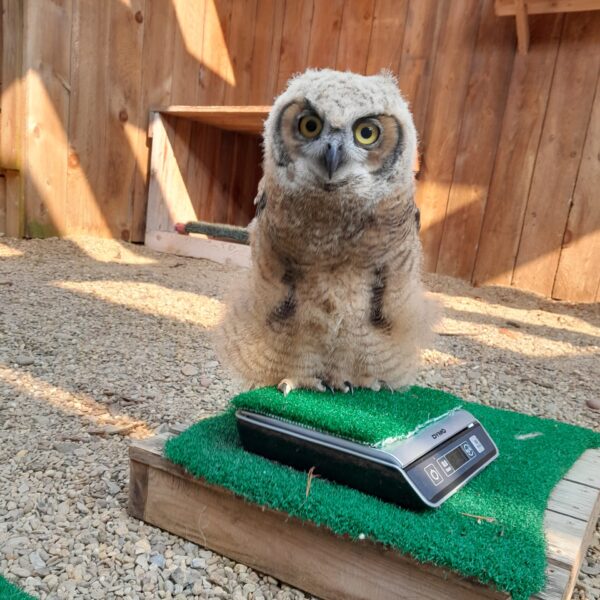

Like with most young ones, play is a great motivator. Sunny has developed a lot of his skills through play, making the experience even more enriching. These skills, such as stepping on a scale, walking into a crate, and perching on a glove, are behaviors that the trainers use to evaluate his health — from tracking how much he weighs, to being able to transfer him in and out of his mew safely, to getting an up-close look at his eyes, cere, mouth, talons, and more. Though offering him the opportunity of choice and control over his body, behavior, and environment takes time and tact, we value that this style of learning will ensure a trusting, positive relationship between owl and trainer.

Great Horned Owlets like Sunny are born in the spring and fledge in the fall. We are using October, lovingly coined “OWLtober,” as a chance to educate our visitors about the amazing animals that owls are, and to reflect on the universal truth that babies do not keep! That sharp growth journey from small, dependent ball of fluff to brave, precisely calculated predator is necessary because being a bird, especially a baby bird, out in the wild, is a beautiful but dangerous thing. We have seen this extremely fast development represented in Sunny’s ability to learn, explore, and adapt through this journey. It has been such a joy to observe him grow and thrive.

Sunny has had the warmest welcome thanks to this caring community. He has already awed and wowed hundreds of visitors who have come to the Center just to see him, and those who frequently return to track his growth and development. His impact began the moment he arrived and will continue throughout his lifetime living here at Shaver’s Creek.

If you’d like to learn more about Sunny and his species, stop by Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center this Saturday, October 28, at 11:00 a.m. for our free Meet the Creek Great Horned Owl program!

If you’ve connected with Sunny and would like to support him and his daily care, consider becoming an Honorary Animal Caretaker. Supporters through this program can make the difference in the lives of our resident animals and will also receive a certificate, information card about their supported species, and (for Sunny’s first 60 supporters) a Great Horned Owl plushie!