This spring marked the second year that the staff of Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center (SCEC) and members of the public had the opportunity to observe a nesting pair of barn owls through a live webcam. Two webcams were mounted, one inside and one outside the nest box, for 24/7 observations of the barn owls’ activities from March 1 through June 18. One SCEC staff member and three volunteers observed nocturnal footage, taken every day from evening through morning, and noted food deliveries, copulation, nestling growth, and any noteworthy behavior. Observations of the second full nesting season gave our observers further insight into the daily activities of an experienced barn owl pair as they raised their owlets in a well-managed habitat that provided suitable nesting and hunting opportunities. Observing consecutive nesting seasons allowed our observers to compare and to contrast mating, incubation, hatching, feeding, and fledging trends with various weather patterns and nest box–management choices while engaging with the community to connect them to the natural world.

The 2019/2020 winter season exhibited slightly higher-than-average temperatures. The historical average high temperatures for December, January, and February for Mifflin County respectively are 40°F, 36°F, and 40°F; whereas this winter, the recorded average high temperatures were 41°F, 41°F, and 43°F. Additionally, the historical average low temperatures for this region during these months respectively are 25°F, 20°F, and 22°F; whereas this winter, the recorded average low temperatures were 28°F, 26°F, and 29°F. This region also exhibited significantly lower-than-usual precipitation for the winter months. The historical average precipitation values for December, January, and February respectively are 2.97”, 2.74”, and 2.42”. The recorded average precipitation values for 2019/2020 were 0.13”, 0.11”, and 0.95”. The majority of the precipitation this winter (90%) occurred as rainfall, rather than snowfall. Winters with heavy snowfall and sustained freezing temperatures prevent nocturnal herbivores from foraging, which, in turn, limits food availability to farmland raptors. In this case of a mild winter, there was most likely an abundance of prey items to sustain the barn owl pair throughout the winter, not forcing individuals to migrate to warmer regions. The slightly warmer-than-normal temperatures, coupled with significantly lower-than-average precipitation, allowed this barn owl pair to initiate their breeding season three weeks earlier than last year.

Incubation

The webcam was installed on March 4, and at that time, the female was incubating her first egg. Thereafter, egg laying occurred every two days until March 13 when one egg was placed aside by the female, leaving the nest with four remaining eggs — she most likely perceived that the egg was damaged or defective. Egg laying continued on March 14 with a fifth egg observed, followed by a two-day egg-laying period until March 19, when a full clutch of seven eggs was noted. As in the previous season, this egg-laying total is well within the typical barn owl clutch range (3–11 eggs). This season, the female laid her entire clutch of eggs a full three weeks ahead of last season’s schedule.

Like last season, incubation was performed solely by the female with the male providing food to his mate throughout the incubation period. Before any nestlings hatched, observers noted that the female took brief breaks from incubation (roughly 15–20 minutes per evening). Toward mid-March and through mid-April, as hatching occurred, food delivery frequencies by the male increased twofold. At this time, the female was observed piling up prey items around her to “feather” the nest to prepare a surplus food supply for the nestlings.

Copulatory behavior was observed from early March through mid-April, even after the eggs were laid and especially before the nestlings began to hatch. During this nesting season, copulation occurred up to fourteen times per evening. About 95% of the time when the male brought prey items for his mate, she would accept his advances. Multiple copulations after eggs are fertilized and are laid appear to be a waste of energy; however, this ongoing mating strategy is advantageous if any of the eggs in the clutch are preyed upon or damaged, which could be a reason why the female placed one of the eight eggs aside. Moreover, with the increase in copulatory acts and the rapidly approaching period when the eggs would hatch, the food deliveries and frequencies vastly increased. Copulatory behavior ceased after the fifth nestling was hatched — a trend that was also observed during the previous nesting season. This is most likely due to the drop of the male’s testosterone levels as well as the increased need for the female to assist her mate with feeding the growing brood.

Hatching

Of the seven fully incubated eggs, six of them hatched between April 5 and May 1 with the first four hatchlings emerging over a thirteen-day period. The final two hatchlings emerged within fourteen days after their older siblings. Owls, like other raptors such as hawks and eagles, demonstrate asynchronous egg laying and hatching. Their eggs are laid one at a time over a span of several weeks, and, likewise, the owlets hatch one at a time over a period of several weeks to one month. An asynchronous hatching strategy has two advantages. First, the owl parents can raise the largest number of offspring that can be supported by unpredictable prey populations, and, second, this hatching strategy allows for the survival of the most-fit owlets. However, one disadvantage of asynchronous hatching strategy occurs if there is insufficient incoming prey because of poor weather conditions (e.g., rainstorms or cold snaps). When this occurs, the food supply is not properly allocated to the entire brood, and the older and larger siblings will outcompete the younger and weaker siblings for food and may cannibalize the youngest sibling(s), resulting in smaller-than-usual numbers of owlets surviving to the fledgling stage.

Although this barn owl pair is experienced, efficient, and quite successful in bringing prey to their brood, the youngest and smallest owlet was observed deceased in the nest box on the night of May 9.

A number of reasons for the death have been theorized, but one cannot speculate a “smoking gun.” According to our observations, these are the three primary reasons:

- The older siblings may have outcompeted the youngest for food items, leading to starvation.

- The female parent reduced her presence in the nest box. From our observations, the male was the sole food provider until May 3. Before this date, the female remained in the nest box during all hours of the day with the owlets, tearing apart the delivered food items and assisting with body warmth. In early May, when the third owlet was large enough to feed itself, the female began assisting her mate with food delivery to the brood. This nearly doubled the number of prey items delivered but reduced her presence in the nest box. On May 7, observers noted for the first time that the female did not roost in the nest box during the day. Thereafter, she significantly reduced her time in the nest box, eventually becoming completely absent while choosing to roost in a nearby abandoned silo with the male counterpart.

Observers noted this behavior during the 2019 nesting season and theorized that the female decreased her presence in the nest box due to growing nestlings and overcrowding in the nest box. For the 2020 nesting season, SCEC staff modified the nest box with increased width and height in the hopes that the female would reside longer to assist with parental care. Unfortunately, this did not hold true. During the 2019 season the female began roosting outside the nest box 29 days after the first egg hatched. During the 2020 season, this was noted at 33 days, indicating this parental behavior is not affected by nest box size, but could be due to developmental stages in owlets. According to the Barn Owl Trust, at three weeks owlets begin replacing the birth down feathers with a thicker down that assists with keeping them warm without the presence of either parent.

- The first week of May brought unexpected and below-average temperatures to the region. Low temperatures on May 4, May 5, May 6, May 7, May 8, and May 9 reached 45°F, 37°F, 39°F, 32°F, 32°F, and 27°F, respectively. This can cause significant challenges for newborn owlets that have not been given time to grow proper down feathers and to develop effective food-consumption skills.

Feeding

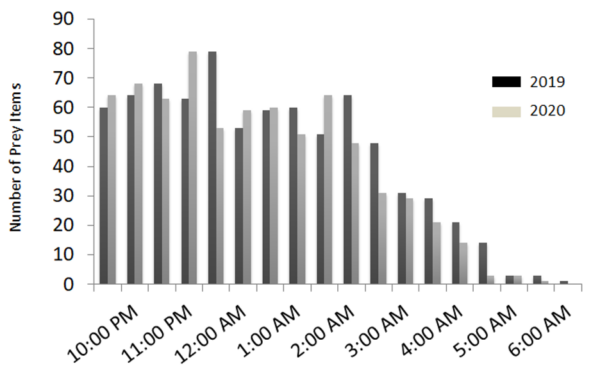

Our observations (Figure 1) showed that peak feeding times occurred from 10:00 p.m. to 11:30 p.m. and from 1:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. The owls’ peak feeding times this season were consistent with last season. Our observations also reveal that barn owls are strictly nocturnal in their hunting and feeding habits. Clear, dry, and moonlit skies are the most optimal conditions for hunting, as nocturnal herbivores take advantage of foraging opportunities. Overcast, rainy, and stormy weather significantly decreases feeding frequencies and quantities of food (by about half) delivered to the owlets. Variable weather conditions explain some of the nightly variations in prey-item deliveries to the nest box.

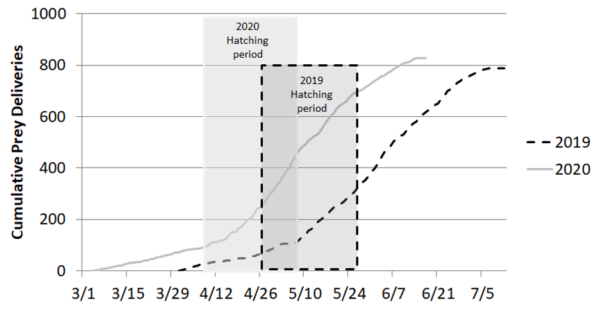

Studies have shown that the top prey choices for barn owls are meadow mice, house mice, Norwegian rats, common shrews, and small songbirds. This season, observers were able to identify two starlings and two cottontail rabbits along with the usual rodents that made up the vast majority of prey items delivered to the nest box. In 2020, a total of 826 food items were counted as food deliveries from the male to the incubating female or from one or both parent(s) to the growing owlets. In 2019, 788 food items were counted as food deliveries. Additionally, even though the webcam was not operational last year until the second egg was laid, the cumulative prey delivery patterns are consistent between the two seasons. Moreover, there was one fewer owlet in this season’s brood than in the previous season; however, the cumulative prey deliveries (Figure 2) followed a similar pattern from 2019. Observations from this spring as well as from the previous spring will give educators and landowners a sense of the significance a barn owl pair raising a clutch of 4–7 nestlings can have in the consumption of rodents in a given habitat.

Fledging

Owlets are not pushed out of their nest sites by their parents. Growth hormones surge in adolescent owlets, signaling when they are ready to fledge. Their feathers and wings are fully developed; however, they are not strong enough for sustained flight, so owlets will “branch” from one potential landing or perching site to the next one, to build up flight endurance. Using the outside webcam near the nest-box entrance, observers noted that the owlets perched themselves upon the entranceway opening on the outside of the nest box and then held on until they were ready to leap upon two man-made platforms mounted outside of the nest box. At this time, the owlets flapped their wings to build strength and to practice take-off and landing techniques. Sometimes the owlets would fall to the ground and then they would fly or climb back up onto either platform and try again. The oldest owlet began flapping its wings inside the nest box’s entryway to begin the fledging process on June 3. The owlets’ “flight school” practices were observed over a fifteen-day period beginning with the first four fledges on June 6 and June 7 and ending with the last fledging on June 18. Typically, the three oldest owlet siblings who learned to fly first would be out most of the evenings foraging and then return before dawn to join the youngest siblings for diurnal roosting. Around mid-June the oldest owlet sibling began roosting outside of the nest box at an unknown location. Soon after, the younger owlets followed suit. The oldest owlet typically left at about 9–12 weeks of age, approximately a few days earlier than the next oldest owlet. Observers noted that all the owlets did not leave the nest box permanently until the youngest sibling fledged in late June.

Dispersal

Once the owlets leave the nest box permanently, they individually disperse. According to Barn Owl Trust, depending on when the eggs are laid, owlet dispersal can be as early as late June or as late as December; however, dispersal typically occurs from August through November. Additionally, the length of time owlets stay within their fledging territory and roosting sites depends on three factors: 1) the available food supplies, 2) the abundance of dry roost sites, and 3) the presence of an unpaired barn owl of the opposite sex.

Once the youngest owlet fledged in late June, the landowner reported that all six owlets roosted around the barn and silo during daylight hours. Dispersal is not well understood at this location, and more information is needed to determine if their dispersal patterns follow a defined trend. Through observations and by placing aluminum bands on individual birds, we can assist in understanding this behavior.

Acknowledgments

A big thank you to the private landowners for providing the opportunity to share the barn owls’ nesting success this season with the community at large and for providing suitable nesting and foraging opportunities. Thank you to SCEC’s Assistant Program Director Jon Kauffman and to volunteers Lou Saporito, Alison Sepkovic, and Traci Sepkovic for contributions of their time perusing and analyzing video footage and compiling this season’s summary. Another big thank you to Steven Sharp for offering his time to proofread and edit this season’s summary.

Funding for this project and other STEM activities was provided by the M. W. McBride endowment for Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center and was greatly appreciated.

What a terrifically informative piece of reportage, based on the tireless, fruitful research of Carolyn Muse and her intrepid team. Huge kudos to Carolyn and Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center!

Very, very cool. Something is making round holes on my barn, I was told they were bees or woodpecker. Maybe it is an owl, do they bore their own holes or look for openings? Thank you for these nice videos.